The Living Word: A Journey Into the Heart of Islamic Manuscripts

Imagine a world without the hum of digital devices, a world where knowledge was not a click away but a treasure hunted, crafted, and preserved by hand. In this world, the most profound ideas—the whispers of philosophers, the formulas of scientists, the verses of poets, and the revelations of prophets—were entrusted to parchment and paper. They were not merely written; they were born through a sacred collaboration of mind, hand, and heart. These objects of breathtaking beauty and profound intellect are Islamic manuscripts, and they are far more than relics of a bygone era. They are living bridges to a civilization that shaped our modern world.

For centuries, from the sun-baked shores of Spain to the bustling ports of Indonesia, a remarkable intellectual revolution was meticulously recorded in ink. Islamic manuscripts became the vessels carrying the legacy of one of history’s most prolific and vibrant scholarly traditions. They are a testament to a culture that revered the written word, not only as a means of communication but as an art form in itself, a physical manifestation of divine and human wisdom. This journey into their world is not just an exploration of the past; it is a key to understanding a rich cultural heritage that continues to inform and inspire millions today. As custodians of this legacy, institutions like The Islamic Manuscripts Press of Leiden (IMPL) play a crucial role in ensuring these silent voices continue to speak to us, offering lessons from a time when scholarship knew no borders.

The Bedrock of a Civilization: More Than Just Ink on Paper

To call an Islamic manuscript a “book” is like calling a cathedral a “building”—it is technically correct but misses the entire essence of its soul. In the Islamic world, the manuscript was a holistic object that engaged the intellect, the spirit, and the senses. Its creation was an act of piety, a pursuit of knowledge (ʿilm), and a demonstration of artistic excellence, all rolled into one.

The very materials used were chosen with care. Parchment, made from animal skin, was the early champion, prized for its durability. Then came paper, a technology embraced from China and perfected in legendary mills in Samarkand and Baghdad. This wasn’t the wood-pulp paper of today; it was often made from linen or cotton rags, giving it a strength that has allowed these volumes to survive for a millennium. The ink, too, was a product of sophisticated chemistry. Scribes concocted it from gall nuts, soot, or even precious metals, creating a rich, black substance that has defied the fading power of centuries. The preparation of a manuscript was, in itself, a scientific and ritualistic process, setting the stage for the words that would grace its pages.

The Scribe’s Sacred Duty: Where Penmanship Met Devotion

Before the printing press standardized typefaces, the human hand was the sole engine of reproduction. The scribe (warraq or kātib) was not a mere copyist; he was a scholar, an artist, and a craftsman. His work was considered a form of worship. It was common for a scribe to begin his work with the basmala: “In the name of God, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful,” infusing the entire endeavor with a sacred intention.

The development of Arabic calligraphy into a supreme art form is directly linked to this reverence for the word, particularly the words of the Qur’an. It was believed that beautiful writing honored the divine message. Over time, a family of distinct scripts evolved, each with its own personality and purpose:

- Kufic: The earliest and most majestic, characterized by its angular, upright forms. It was the script of the first Qur’ans and official inscriptions, radiating a powerful, timeless authority.

- Naskh: The workhorse of the manuscript world. Its clear, legible, and cursive style made it perfect for copying long texts, from legal treaties to literary masterpieces. It is the ancestor of most modern Arabic print fonts.

- Thuluth: The script of grandeur. With its elegant, soaring verticals and complex curves, it was used for titles, chapter headings, and architectural decoration.

- Nastaʿlīq: The “bride of calligraphy.” Born in Persia, this script is instantly recognizable for its sweeping, rhythmic flow, as if the words are dancing across the page. It became the preferred script for Persian, Ottoman Turkish, and Urdu poetry.

The scribe’s life was one of immense discipline. A single mistake could mean starting an entire page over. This painstaking process ensured an intimate connection between the copyist and the text, a far cry from the passive act of photocopying. Each manuscript was a unique performance of a timeless work.

A Symphony of Color and Gold: The Art of Illumination

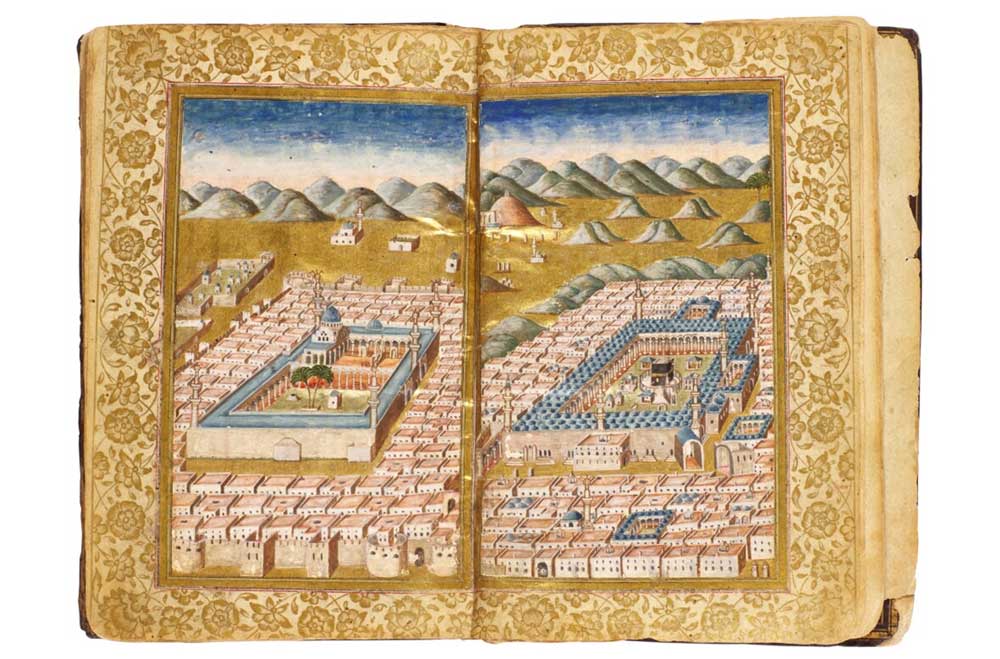

If calligraphy was the voice of the manuscript, then illumination was its music. The term “illumination” refers to the intricate and colorful decorative elements that adorn a manuscript. Far from being mere decoration, this art served specific purposes: to honor the text, to guide the reader, and to represent the beauty of paradise.

The most spectacular illumination is often reserved for the sacred. Opening pages of a Qur’an could be a blaze of gold and lapis lazuli, with geometric patterns and arabesques (intertwining vines and foliage) creating a visual prelude to the divine words within. These designs were not random; they were deeply symbolic. Geometric patterns reflected the infinite and orderly nature of God’s creation, while arabesques, with their endless, repeating lines, symbolized the eternal cycle of life.

But illumination was also practical. It acted as a sophisticated reading aid. A chapter heading, or sūrah, would be announced with an elaborate panel. A rosette or a palmette in the margin might mark a verse division or a point for prostration. In scientific or literary texts, key passages might be emphasized with gilded frames or illustrated diagrams. The palette was often rich and symbolic: gold for light and divinity, lapis lazuli for the heavens, and vermilion for importance.

Beyond the Sacred: The Incredible Diversity of Subjects

While the production of magnificent Qur’ans is the most celebrated aspect of the Islamic manuscript tradition, to stop there would be to see only one star in a vast galaxy. The range of subjects covered is simply staggering and shatters any monolithic view of Islamic civilization.

- The Sciences: While Europe was in its so-called “Dark Ages,” the Islamic world was a beacon of scientific inquiry. Manuscripts preserved and expanded upon the knowledge of the Greeks, Persians, and Indians.

- Medicine: Ibn Sīnā’s (Avicenna) The Canon of Medicine was a standard medical text in Europe for over 500 years. Manuscripts of it are filled with detailed diagrams of the human body, surgical instruments, and descriptions of diseases.

- Astronomy: Works by al-Ṣūfī and al-Bīrūnī contained precise star charts and discussions of planetary motion. Astrolabes were often depicted and described in intricate detail.

- Mathematics: Al-Khwārizmī’s texts introduced algebra (from the Arabic al-jabr) to the world. Manuscripts show the development of the decimal system and the fascinating world of geometric proofs.

- Literature and Poetry: This is where the human spirit truly soared. The epic Shahnameh (Book of Kings) of Ferdowsi was transformed into some of the most lavishly illustrated manuscripts ever created, with miniatures depicting heroic battles and tragic romances. The poetry of Rūmī, Ḥāfiẓ, and Saʿdī was copied and recopied, their mystical and romantic verses often accompanied by delicate paintings.

- History and Geography: Scholars like Ibn Khaldun, with his revolutionary theory of history in the Muqaddimah, and travelers like Ibn Baṭṭūṭa, who recorded his journeys from Mali to China, provided the world with new understandings of society and space.

- Philosophy and Mysticism: The works of al-Ghazālī, known as “The Proof of Islam,” explored theology and philosophy, while Sufi masters recorded their mystical experiences and poetry, seeking to map the journey of the soul toward God.

This incredible diversity proves that the Islamic manuscript tradition was a global, interdisciplinary project long before the term was invented. It was a continuous conversation across continents and centuries.

The Library of a King and the Notebook of a Student: A Spectrum of Patronage

Who paid for all this? The creation of a fine manuscript was expensive, requiring the labor of paper-makers, calligraphers, illuminators, and bookbinders. The system that supported this was patronage.

At the top were the great royal libraries. The legendary House of Wisdom (Bayt al-Ḥikmah) in Abbasid Baghdad was more than a library; it was a research institute, a translation bureau, and a magnet for the greatest minds of the age. Similar centers flourished in Cairo, Istanbul (under the Ottoman Sultans), Isfahan, and Delhi. A ruler’s prestige was measured not only by the size of his army but by the depth of his library.

But manuscripts were not only for the elite. Wealthy merchants and local governors also commissioned books, creating a vibrant urban market for scribes and artists. Furthermore, the Islamic system of charitable endowments (waqf) often included libraries, making knowledge accessible to students and scholars. A student might not own a lavishly gilded Qur’an, but he could copy his own textbook, creating a humble yet vital part of the manuscript ecosystem. This multi-tiered system of patronage ensured that the production of knowledge was both a pinnacle of high culture and a grassroots intellectual activity.

The Modern Challenge: Preservation in the Digital Age

Centuries after their creation, these manuscripts face new threats. The very paper that has survived for so long is now vulnerable to acidity, pollution, and fluctuating humidity. The bindings, once so strong, are now fragile. The task of preservation is a race against time, requiring a blend of traditional craft and cutting-edge science.

Conservators in laboratories around the world work with surgical precision to repair torn pages, neutralize acidic paper, and re-back crumbling bindings. They use tools like multispectral imaging to read texts that have been erased or damaged beyond the capability of the naked eye. This technology has revealed palimpsests—manuscripts where the original text was scraped off and written over—unlocking lost works of antiquity hidden beneath later writing.

This is where the mission of The Islamic Manuscripts Press of Leiden (IMPL) becomes critically important. Preservation is not just about saving the physical object; it is about saving the knowledge and the artistry it contains. By producing meticulous published editions of these salient works, IMPL ensures that the intellectual content is rescued from the fragility of a single, aging codex. They transform a unique, inaccessible treasure into a shared, global resource for scholars and the public alike.

A Bridge to the Present: Why Manuscripts Matter Today

In our age of digital ephemera, where texts are deleted as quickly as they are created, the Islamic manuscript stands as a powerful antidote to our collective amnesia. It teaches us profound lessons that are more relevant than ever.

It is a testament to cultural dialogue. These manuscripts show us that the great leaps in human knowledge have never occurred in isolation. The Islamic world was a great synthesizer, connecting the knowledge of Greece, India, Persia, and China, and then passing it on, enriched and expanded, to Europe and beyond. They are a permanent rebuke to the idea of a “clash of civilizations,” reminding us of a long history of intellectual exchange.

They are a monument to slow knowledge. The careful, deliberate process of the scribe stands in stark contrast to our culture of haste. It reminds us that deep understanding and lasting beauty require time, patience, and focused attention.

Most importantly, they give a human face to history. A marginal note from a frustrated student, a fingerprint in the ink, a dedication from a proud patron—these small, human traces connect us directly to the people of the past. They were not abstract figures; they were individuals who laughed, wondered, argued, and sought meaning, just as we do.

The silent, patient work of cataloging, conserving, and digitizing these manuscripts, as undertaken by institutions and dedicated scholars worldwide, is one of the most important cultural projects of our time. It is an act of global citizenship, ensuring that this immense and shared heritage remains a living, breathing source of wisdom, beauty, and inspiration for all humanity.

A Note on The Islamic Manuscripts Press of Leiden (IMPL)

The journey of understanding and preserving Islamic manuscripts is greatly advanced by the dedicated work of specialized academic presses. The Islamic Manuscripts Press of Leiden (IMPL) stands as a notable contributor to this field. Focused on producing published editions of salient works of Islamic scholarship, IMPL directly addresses the crucial need to transform unique, often fragile manuscript sources into stable, accessible, and critically analyzed printed (and increasingly, digital) formats. The press’s work involves meticulous transcription, translation, and scholarly commentary, making complex historical texts available for a new generation of students, researchers, and anyone interested in the deep intellectual traditions of the Islamic world. The very subject of this article—the beauty, diversity, and intellectual wealth contained within Islamic manuscripts—is the raw material from which IMPL creates its enduring contributions to global knowledge. By supporting such endeavors, we all participate in the ongoing preservation and appreciation of this irreplaceable cultural heritage.

References

- Blair, Sheila S. Islamic Calligraphy. Edinburgh University Press, 2008.

- Bloom, Jonathan M. Paper Before Print: The History and Impact of Paper in the Islamic World. Yale University Press, 2001.

- George, Alain. The Rise of Islamic Calligraphy. Saqi Books, 2010.

- The David Collection, Copenhagen. “Islamic Manuscripts.” https://www.davidmus.dk/en/collections/islamic/materials/manuscripts

- The British Library. “Discovering Sacred Texts: Islam.” https://www.bl.uk/sacred-texts/articles/islam

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “The Art of the Qur’an: Treasures from the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts.” https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2016/art-of-the-quran

- UNESCO. “Memory of the World Register.” https://en.unesco.org/programme/mow

- Digital access portals like:

- The Qatar Digital Library: https://www.qdl.qa/

- The Walters Art Museum Manuscripts: https://www.thewalters.org/collections/manuscripts/

- Schimmel, Annemarie. Calligraphy and Islamic Culture. New York University Press, 1990.

- Contadini, Anna. Arab Painting: Text and Image in Illustrated Arabic Manuscripts. Brill, 2007.