Beyond the Page: A Journey Through the Major Islamic Manuscripts That Shaped Civilization

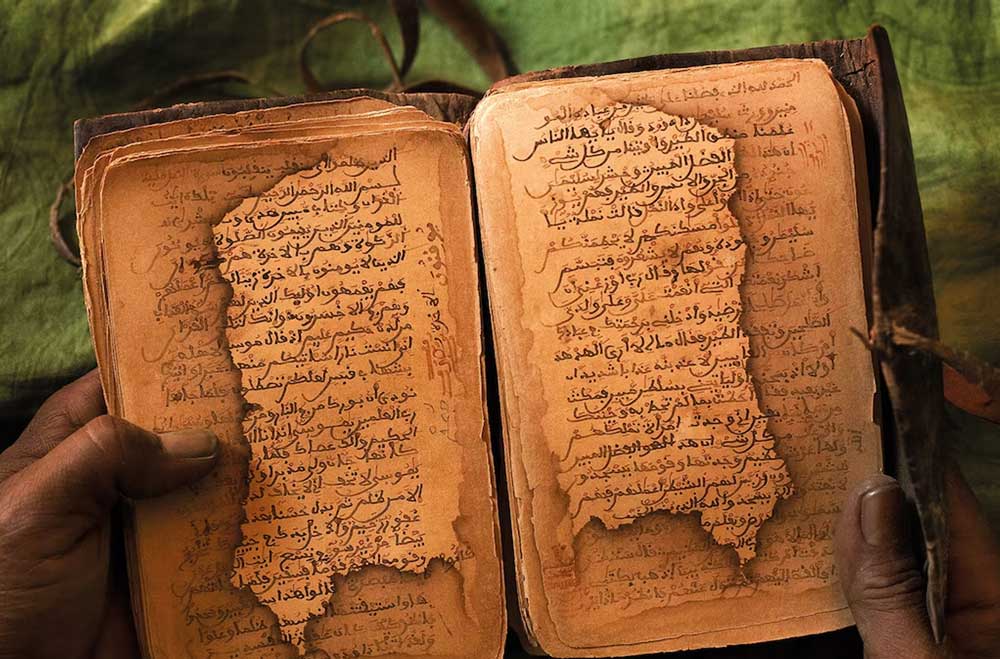

Imagine a world where books were not mass-produced on printing presses, but were born from the patient, devout work of human hands. Each one was a unique treasure, a fusion of profound intellect and breathtaking artistry. In the Islamic world, from the 7th century onwards, manuscripts became the primary vessels of knowledge, carrying not just the sacred word of the Qur’an, but the entire spectrum of human inquiry—from medicine and astronomy to poetry and philosophy. These weren’t merely books; they were portable universities, art galleries, and scientific laboratories, all bound together.

When we ask, “What are the major Islamic manuscripts?” we are really asking a much bigger question: What are the foundational texts that built a civilization? The answer reveals a global, interconnected, and stunningly sophisticated world of scholarship. It’s a story that stretches from the royal libraries of Muslim Spain to the bustling scriptoriums of Mughal India, a story that The Islamic Manuscripts Press of Leiden (IMPL) is dedicated to preserving by producing published editions of these very salient works of Islamic scholarship. This journey will introduce you to the rock stars of this tradition—the iconic manuscripts whose influence echoes through the centuries.

The Sacred Foundation: The Qur’an and the Art of the Book

Any discussion of major Islamic manuscripts must begin with the Qur’an. For Muslims, it is the literal, unchanging word of God as revealed to the Prophet Muhammad. This divine origin story fueled an unparalleled reverence for the physical book itself, transforming its production into the highest form of artistic and spiritual expression.

- The Blue Qur’an: Perhaps one of the most visually striking manuscripts in the world. Created in the 9th or 10th century, likely in North Africa or Persia, this Qur’an is famous for its stunning indigo-dyed parchment pages, upon which verses are written in shimmering gold ink. The effect is celestial, evoking a starry night sky. It wasn’t just a book to be read; it was an object of meditation, a physical representation of the divine’s magnificence. You can view some of its surviving pages on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s website.

- The Timurid and Ottoman Grand Qur’ans: Under royal patronage in empires like the Timurid (Central Asia) and the Ottoman (Turkey), the production of Qur’ans reached new heights of scale and opulence. These were often massive, multi-volume sets written in exquisite calligraphic styles like Muhaqqaq and Naskh, and illuminated with intricate geometric and floral patterns in gold and lapis lazuli. They were statements of imperial piety and power, intended for grand mosques and palaces.

The art of the Qur’an established the aesthetic and technical standards—masterful calligraphy, complex illumination, and luxurious materials—that would influence all other manuscript production.

The Scientific Revolution: Manuscripts That Mapped the World and the Stars

While Europe was in its early medieval period, the Islamic world was experiencing a scientific golden age. Major manuscripts from this era weren’t just preserving knowledge; they were actively expanding it.

- Kitāb Ṣuwar al-Kawākib (The Book of Fixed Stars) by al-Ṣūfī (10th century): This masterpiece of astronomy is more than just a text; it’s a beautiful fusion of scientific precision and artistic illustration. Al-Ṣūfī updated Ptolemy’s star catalog, comparing Greek knowledge with direct Arab astronomical observation. The accompanying illustrations depict the constellations both as they appear in the sky (as dots) and as the mythological figures they represent (e.g., Andromeda, Hercules), making it a vital link between classical and modern astronomy. A digitized version can be explored through the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

- al-Qānūn fī al-Ṭibb (The Canon of Medicine) by Ibn Sīnā (Avicenna) (11th century): For over 500 years, this was the single most important medical textbook in both the Islamic world and Europe. It was a systematic encyclopedia of all medical knowledge available at the time, covering anatomy, pathology, pharmacology, and more. Countless manuscripts of the Canon were copied, studied, and annotated, forming the backbone of medical education. Its influence is hard to overstate.

- Kitāb al-Ḥayawān (The Book of Animals) by al-Jāḥiẓ (9th century): A foundational work of zoology, biology, and even early evolutionary thought. Al-Jāḥiẓ’s work, based on observation and critical thinking, explores animal behavior, adaptation, and the food chain. Manuscripts of this text represent the spirit of inquisitive scholarship that defined the era.

The Epic Tales: Where Literature and Art Collide

If science engaged the mind, epic poetry stirred the soul. Nowhere is this more evident than in the magnificent illustrated manuscripts of the Shahnameh.

- The Shahnama (Book of Kings) by Ferdowsi (10th-11th century): This Iranian national epic, spanning the mythic history of Persia from creation to the Arab conquest, was a perennial favorite for royal patronage. The most famous copies, like the Great Mongol Shahnameh (also known as the Demotte Shahnameh) produced in the 14th century, are landmarks of Islamic art. Their full-page miniatures are explosions of color and drama, depicting heroic battles, tragic romances, and courtly intrigues with breathtaking detail. These manuscripts are a perfect example of how text and image could work together to create an immersive narrative experience.

The Mystical Path: Sufism in Ink

The inner, mystical dimension of Islam, Sufism, also produced profound and beautiful manuscripts.

- The Dīwān of Hafez and The Masnavi of Rumi: The poetic works of masters like Hafez and Rumi were, and still are, immensely popular. Manuscripts of their dīwāns (collected poems) were often produced with delicate illumination. While less lavishly illustrated than the Shahnameh, their beauty lies in the exquisite calligraphy, worthy of the sublime content. These were personal books for contemplation, their words serving as a guide for spiritual ascent.

- Sufi Theoretical Works: Manuscripts of texts like al-Ghazālī’s Iḥyāʾ ʿUlūm al-Dīn (The Revival of the Religious Sciences) were widely copied and studied. They provided the philosophical and practical framework for the Sufi path, and their dissemination through manuscripts helped spread Sufi orders across the Islamic world.

The Administrative Backbone: History, Geography, and Law

A vast civilization needed more than science and poetry; it needed manuals for governance, history, and law.

- al-Muqaddimah (The Introduction) by Ibn Khaldun (14th century): A work so revolutionary it is considered the foundation of modern historiography, sociology, and economics. In it, Ibn Khaldun analyzes the rise and fall of civilizations, introducing concepts like social cohesion (asabiyyah). Manuscripts of the Muqaddimah represent a seismic shift in how humans thought about their own history.

- Kitāb al-Masālik wa-al-Mamālik (The Book of Routes and Realms): This genre of administrative geography, pioneered by scholars like al-Istakhri and Ibn Hawqal, produced manuscripts filled with maps and descriptions of the trade routes and provinces of the Islamic world. These were practical guides for merchants and officials, but their “atlas” format, with its distinct circular world maps, is instantly recognizable and a major contribution to cartography.

- Legal and Hadith Compilations: Manuscripts of foundational legal texts, like al-Bukhari’s Ṣaḥīḥ (a collection of the Prophet’s sayings and actions) and al-Muwatta’ of Imam Malik, were the bedrock of Islamic law and society. Their precise transmission was of paramount importance, and they were copied with extreme care for accuracy.

Conclusion: A Living Legacy in a Digital Age

The story of these major Islamic manuscripts is not confined to the past. They form a collective inheritance for all of humanity, a testament to a time when scholars from diverse backgrounds—Arab, Persian, Turk, Berber, and many others—shared a common language of knowledge. They remind us that the pursuit of understanding is a universal human impulse, one that can produce works of both sublime beauty and rigorous intellect.

Today, the fragile pages of these manuscripts face new challenges from time and environment. This is where the mission of modern scholarship becomes critical. The work of The Islamic Manuscripts Press of Leiden (IMPL) is a direct continuation of this ancient tradition of knowledge preservation. By producing meticulous critical editions, translations, and studies of these major works, IMPL ensures that the intellectual fire contained within these precious manuscripts is not extinguished, but is instead shared, studied, and appreciated by a global audience. They are transforming unique, vulnerable artifacts into stable, accessible resources, guaranteeing that the conversation started over a millennium ago continues to inspire generations to come.

References

- Blair, Sheila S. Islamic Calligraphy. Edinburgh University Press, 2008.

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “The Art of the Qur’an: Treasures from the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts.” https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2016/art-of-the-quran

- Bibliothèque nationale de France. “Shahnama.” https://gallica.bnf.fr/

- The Khalili Collections. “The Arts of the Islamic World.” https://www.khalilicollections.org/

- The British Library. “The Shahnameh.” https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/the-shahnamah

- UNESCO. “Memory of the World Register.” https://en.unesco.org/programme/mow

- The Walters Art Museum. “Islamic Manuscripts.” https://www.thewalters.org/collections/manuscripts/

- The David Collection, Copenhagen. “Islamic Manuscripts.” https://www.davidmus.dk/en/collections/islamic/materials/manuscripts

- Gutas, Dimitri. Greek Thought, Arabic Culture: The Graeco-Arabic Translation Movement in Baghdad and Early Abbasid Society. Routledge, 1998.

- The Digital Hammurabi. “Corpus Coranicum.” https://corpuscoranicum.de/en/